This “Scaling a School” series is a topic I will return to intermittently in the newsletter. The goal is to expose some of the tensions involved when scaling a school & explore how different institutions resolve them. We’ll start by exploring concepts like product-market fit & the best practices of program design and eventually cover most internal functions.

I’ve worked with many schools and bootcamps over the last decade, and one of the things that has surprised me is that none of them have product-market fit.

To be clear, I don’t mean this to say that all schools are bad or that the system is broken. I’m merely trying to find a provocative way of pointing out that they can’t have product-market fit. Fundamentally they aren’t able to, no school is.

The “strong market demand” from the student isn’t for a school and in the bootcamp space specifically, the “strong market demand” is for a pathway to a better job, and plenty of people wake up needing a better one of those.

This pathway (commonly referred to as “an offering” or “course”) is the connection between the student and the job, and its basic function is to meet the requirements of both. Once it’s able to reliably guide learners to a job it has product-market fit.

But the pathway does all the work here, and it’s success tells you very little about the rest of the school, it simply means that this single pathway works pretty well.

The challenge is that across industries, both the quality of the student population and the requirements for a job vary wildly. The minimum competency level of a Jr developer, for instance, is a much lower bar than say a surgeon, and the incoming students will have very different needs as well. We’re going to spend a few posts examining how changing the input (student) or output (job expectation) requires different structures to support the student along the path.

Essentially what this means for a school is, once it moves past a single program, the school as an entity can no longer have product-market fit: it can only collect pathways— aka “courses”— that do.

While this distinction might seem pedantic, misattributing PMF to the school leads to misconceptions about the real capabilities of a school and can cause serious issues at scale.

Let’s dig in.

Misconception 1: A Great School Can Teach Anyone

When you think of “top schools,” what attribute do they all share?

It’s probably not that they have the best teachers or even the best curriculums. Maybe that tuition is too damn high. Even though I didn’t ask anyone, I’d bet “abnormally tight admissions standards” would be on the list. It’s a high bar to get into a top school, and few make the cut.

And while exclusivity can have many brand benefits, one important pedagogical by-product is that it’s waaaaay easier for a school to have better outputs if they tightly control the inputs. It’s all about the student pathway fit after all.

For instance, let’s say you were teaching a bread-making course that’s 6 weeks long, and the students expect that they’ll be able to come out of the course and bake some classic loaves from the Great British Bake-off. Which of these students do you think would do best in this class?

A. A pastry chef

B. A carpenter

C. A 6-year old?

My answer is the pastry chef.

A group made out of pastry chefs would likely be the easiest group to train, followed (probably) by the carpenters. It’s unlikely that the 6-year olds will ever match the first two groups in terms of baking competence, especially in 6 weeks. That would take a very different program design “path”—likely a longer one and perhaps one with a lot of musical numbers and hand puppets.

The basic principle here again is that some students will have an easier time on the path than others, and so the path has to match the student.

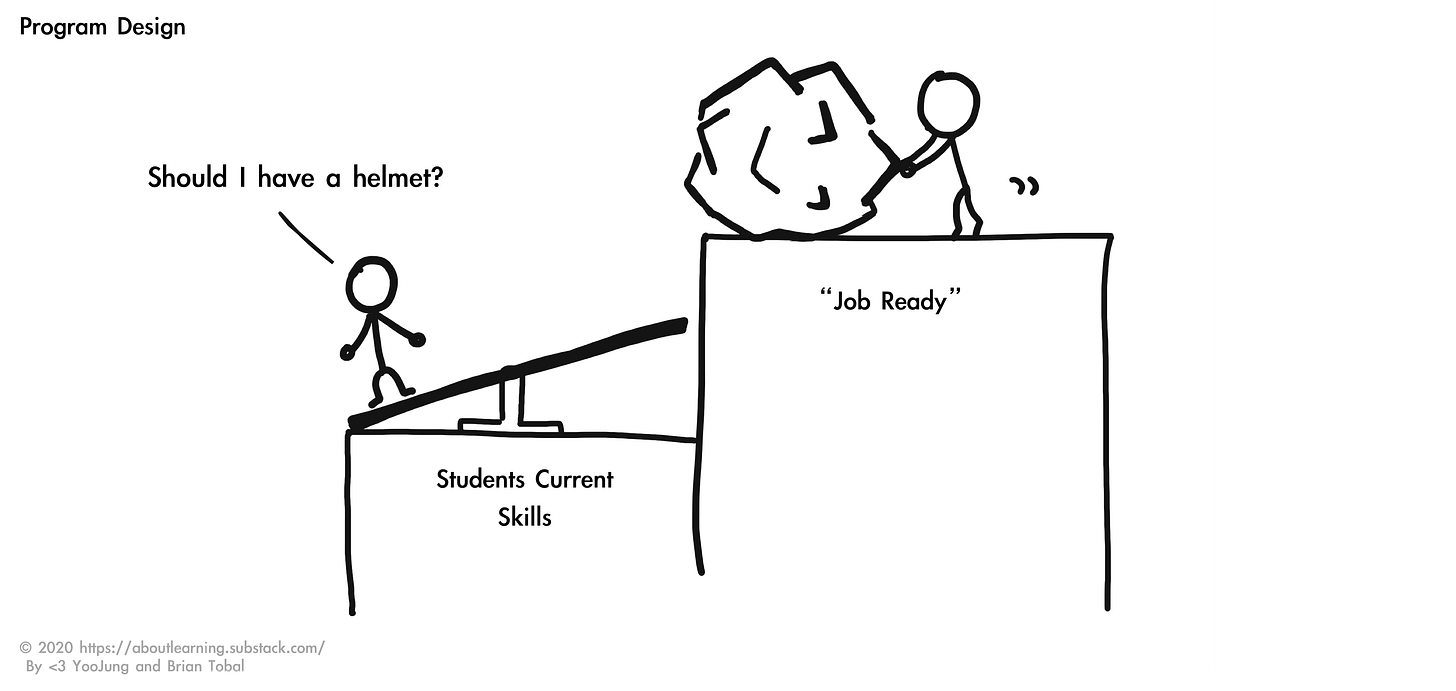

An example of this below:

What can happen for small schools—like a bootcamp—is that they tend to scale by adding more student types to a proven path. Once they have a single successful offering, their natural instinct is to “scale” by putting as many students onto the pathway as they can—whether or not those students are a good fit. The thinking is the institutional “school” has figured this out (PMF) and that in order to grow it just needs to “just stamp out more classes”—fast.

A note from Dr. Michael Hanson

“Also worth noting is that much of education in traditional settings is the influence of peers – if the majority automatically maintain the high standards during the education process that the entrance standards set at the beginning then this feedback loop will have it’s own effects on the pathway as well.”

This is why, on a small scale, bootcamps can be wildly successful. And if they can accurately filter their incoming students for pastry chefs (and learn how to handle a few carpenters in every class) than the quality can hold up over time.

But tension arises with efforts to scale. Even if there are a lot of pastry chefs in the market, they’re not all ready to take your course right now, and so the easiest way to scale is to reduce the focus on student/path fit. Once the admissions organization begins to let in more carpenters, and maybe some 6-year-olds, the next thing you know, finger paint is everywhere.

Most schools don’t recognize this as it’s happening and only notice the after-effects; they think they have a paint removal problem and miss the filtering problem in the admissions department.

The initial impact of poorly-fitting admissions standards is higher dropout rates, more stress on teachers, and typically attention diverts from top students to keep the bottom layer progressing forward on time.

In the future, we’ll cover pedagogical strategies to handle a diverse classroom such as differentiated curriculums and “low bar / high ceiling” but the fact is few schools have the bandwidth to implement such structures now—and no one that I know of has started this work.

If the school continues to admit students who are a bad fit, the good teachers will burn out. It’s not crazy to hear of 50-80% teacher churn in these scenarios, and those instructors who are left tend to water down the curriculum, just so students can pass through without much trouble. At this point, they indeed could indeed teach anyone, but it might not be worth it.

Misconception 2: A Great School Can Teach Any Course

Just like the belief that “our school can work for every student,” this great school fallacy tricks us into believing that we can serve all markets and all topics as well as the flagship offering. It’s all “learning” after all, and we are a great school.

Again, if you assume that the school has PMF, this mentality makes a lot of sense; you’ve got a special sauce that made the first offering go so well. However, this same type of thinking would be like assuming that because Netflix has a hit baking show that every show they produce will be a hit—and a quick perusal of “Nailed It” will hopefully prove my point.

What typically happens is that more courses are “stamped out” by closely mimicking the original path. It feels safer and easier to copy what works than to reason from the first principles about what a topic and input student requires.

In this haste to duplicate the success, it’s often overlooked that different subjects require different tools, timelines, and inputs—and should have different expectations for what a qualified output looks like. This oversight can cause a school to make unreasonable promises to the incoming students, which is really a recipe for public disappointment.

If we take a “pathway as the product” approach, we might start to notice that each pathway requires the same amount of iteration as any new product. Also, a pathways approach shows us that while a school’s special sauce can add to the overall quality of the paths, fundamentally a path is an operational process run by humans, and its quality is distinctly tied to how well the humans run it.

Again this is why early success for a bootcamp can be misleading, an educational path works because of the humans on it and replicating the humans isn’t technologically possible yet.

However, a school can increase the number and reliability of its paths in a few ways. By slow-growing them internally, with small teams and cohorts to allow for quick iteration and decision making with a single product owner who is responsible for the success of their individual pathway. However, the quickest way to scale is just to buy another pathway that has PMF already in a single offering. This comes with other challenges, but the reliability of the pathway’s PMF is worth it.

So what is the value of a school anyways?

Fundamentally, a school’s ability to control the day-to-day happenings across paths is very limited, it’s relying on high-quality humans to do what’s best for the students. It’s real core value beyond basic administration and investing resources wisely, is mostly as an attraction mechanism; i..e can the school attract high-quality candidates in large numbers?

The value of the school is the signal. If a school can achieve signal status, then the probability of each individual student's success will also go up. The market will demand more of them, and a community will form that can network in favors.

Beyond signal though, the physics of the program design rule, and as we’ll see in the next post, these mechanisms are far more relevant than any other factor to a school’s success.

Hopefully, this has been a helpful lens upon which to view schools, and you can now see why they can’t have product-market fit and must rely on collecting pathways— aka “courses”— that do.

Next Post: (Maybe) Responsive Learning using Spaced Repetition

Next in this Series: The Physics of Program Design or “Catapulting Learners to Success”.

Thanks for the great piece Brian. I am curious to know the name of the paper/ article you got Dr. Hanson quote from.